The Ralph Wiggum Experiment

Can a "while loop" make AI a better coder? Explore the Ralph Wiggum technique: a persistent iteration method that successfully automated a DB migration.

The Ralph Wiggum technique has been all over developer X since late 2025. Created by Geoffrey Huntley, it's named after the Simpsons character who embodies "persistent iteration despite setbacks." At its core, Ralph is deceptively simple: a bash loop that keeps feeding an AI agent a task until the job is done.

I've been recently hooked with this idea and decided to actually try it.

The Candidate: Migrating Users, Tenants, and Sites to SQL

Here's what I'm dealing with: a Cosmos DB to Azure SQL migration. The project is moving in a direction where we need relations to make things easier to handle. So I decided to take a small part out of this migration and run it through this methodology. This means to have three interconnected entities with foreign key relationships. The task involved creating EF Core entities and configurations, writing entity-domain mappings, implementing repository pattern classes, building data migration tools, updating DI registrations, verifying infrastructure works, and making sure all unit tests still pass. To be honest, pretty straight forward nothing special. So an ideal candidate.

It is also worth mentioning that sites are nested inside tenant documents in Cosmos. So the migrator needs to extract them into a separate SQL table.

It is more than just "write me a function" kind of task. It takes some hours, even days of implementing and testing the migration.

Setting Up Ralph

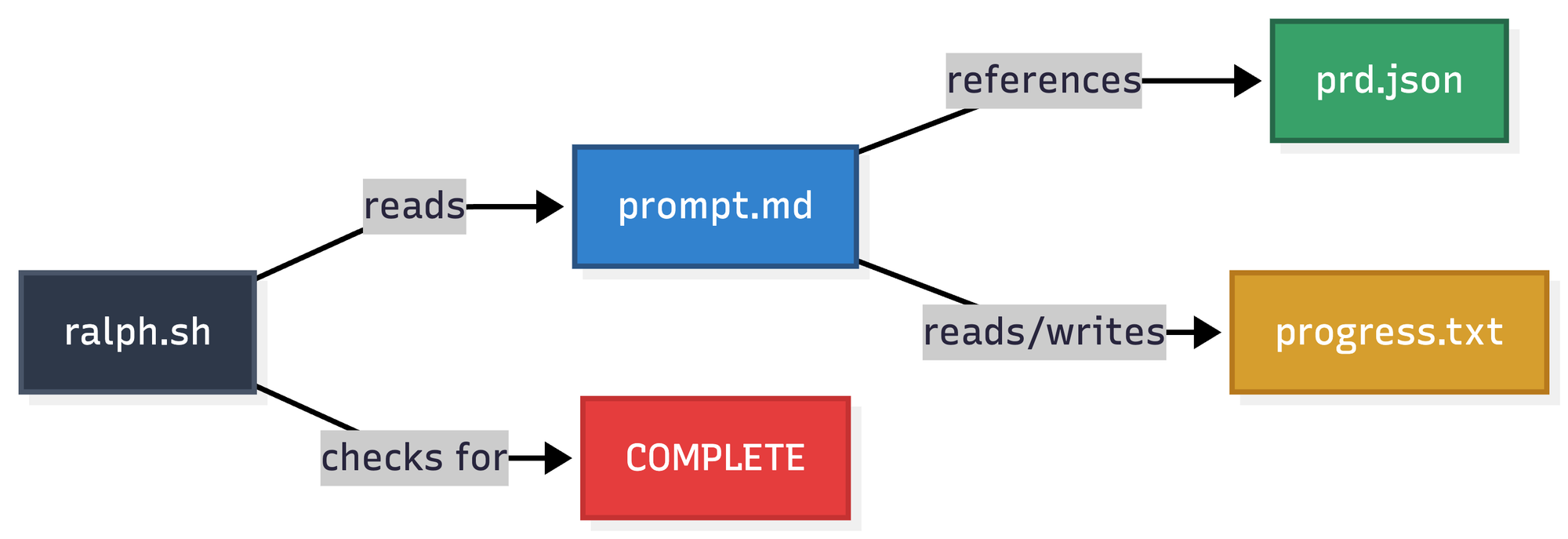

The technique itself is simple. You need five artifacts:

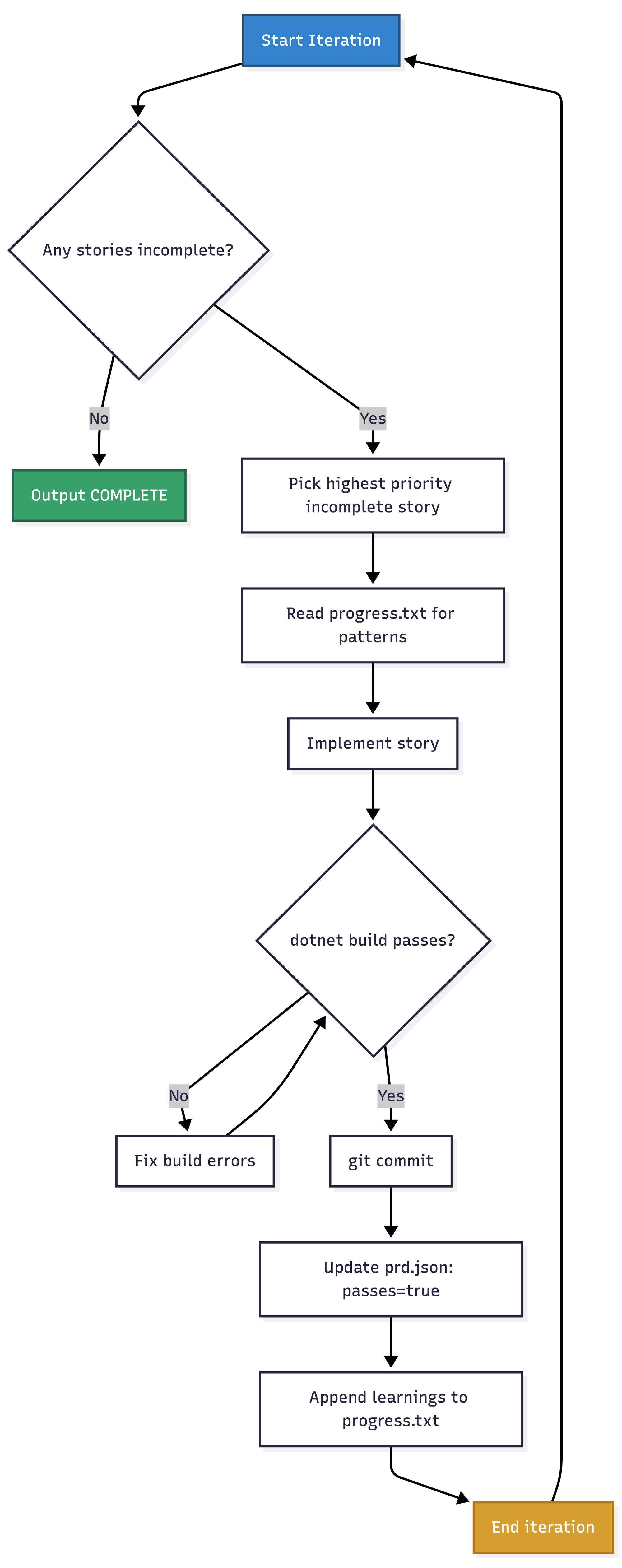

The bash script (ralph.sh) is just a while loop that pipes prompt.md to Claude Code, checks for the completion signal, and repeats. Each iteration, Claude reads the same instructions, picks the next incomplete story from prd.json, implements it, commits, and updates the progress log.

Basically the same loop that I would use to work with Product Backlog Items in Azure Boards.

Here's the simplified loop:

for i in $(seq 1 $MAX_ITERATIONS); do

REMAINING=$(cat prd.json | jq '[.userStories[] | select(.passes == false)] | length')

if [[ "$REMAINING" -eq 0 ]]; then

exit 0

fi

OUTPUT=$(cat prompt.md | claude --dangerously-skip-permissions 2>&1)

if echo "$OUTPUT" | grep -q "<promise>COMPLETE</promise>"; then

exit 0

fi

sleep 5

done

The script keeps running until either all stories are marked complete or we hit the iteration limit.

The Necessity of Small User Stories

Here's what I think makes this work. The prd.json isn't a massive spec document. It's 18 small, focused user stories. Each one has clear acceptance criteria and can be completed in a single iteration.

{

"id": "US-001",

"title": "Create TenantEntity with configuration",

"acceptanceCriteria": [

"TenantEntity.cs exists in backend/Rsu.Infrastructure.Sql/Entities/",

"TenantConfiguration.cs exists in backend/Rsu.Infrastructure.Sql/Configurations/",

"Entity has: Id (Guid PK)",

"JSON columns for: Setup, Subscription, Rules",

"dotnet build succeeds"

],

"passes": false

}

The key constraints are: one story per iteration, build must pass before commit, and the agent updates its own tracking files.

This matches something I've been thinking about for a while: overly detailed AI-generated plans are a primary cause of agent failures. By breaking the work into small chunks with explicit "done" criteria, each iteration stays focused.

This isn't new. We should practice this already when writing product backlog items or github issues. But we don't. Being forced to think in such small steps makes it possible to let the AI run and self iterate.

The Progress Log: Memory That Persists

The second crucial piece is progress.txt. It starts with patterns and constraints:

## Codebase Patterns

### EF Core 10 Patterns

- Use primary constructor pattern for DbContext

- JSON columns use `builder.OwnsOne().ToJson()` or `builder.OwnsMany()`

- Entities go in `Entities/` folder, configurations in `Configurations/` folder

### Network Constraints (CRITICAL)

- Azure SQL is VNET-isolated, no public access

- EF migrations run via Container App Job inside VNET

Each iteration, the agent appends what it learned:

## 2026-01-08 - US-003

- Expanded UserEntity with all fields from domain User model

- Files changed: UserEntity.cs, UserConfiguration.cs

- **Learnings:**

- Expression trees in EF Core can't use C# 12 collection expressions

- Must use `new List<T>()` instead of `[]` syntax

- For nested owned types in JSON columns, use nested OwnsOne calls

Problems discovered in US-003 prevent the same mistake in US-007. The context accumulates.

Trust the Loop - Let Claude Code Run

Sounds crazy, what could go wrong?

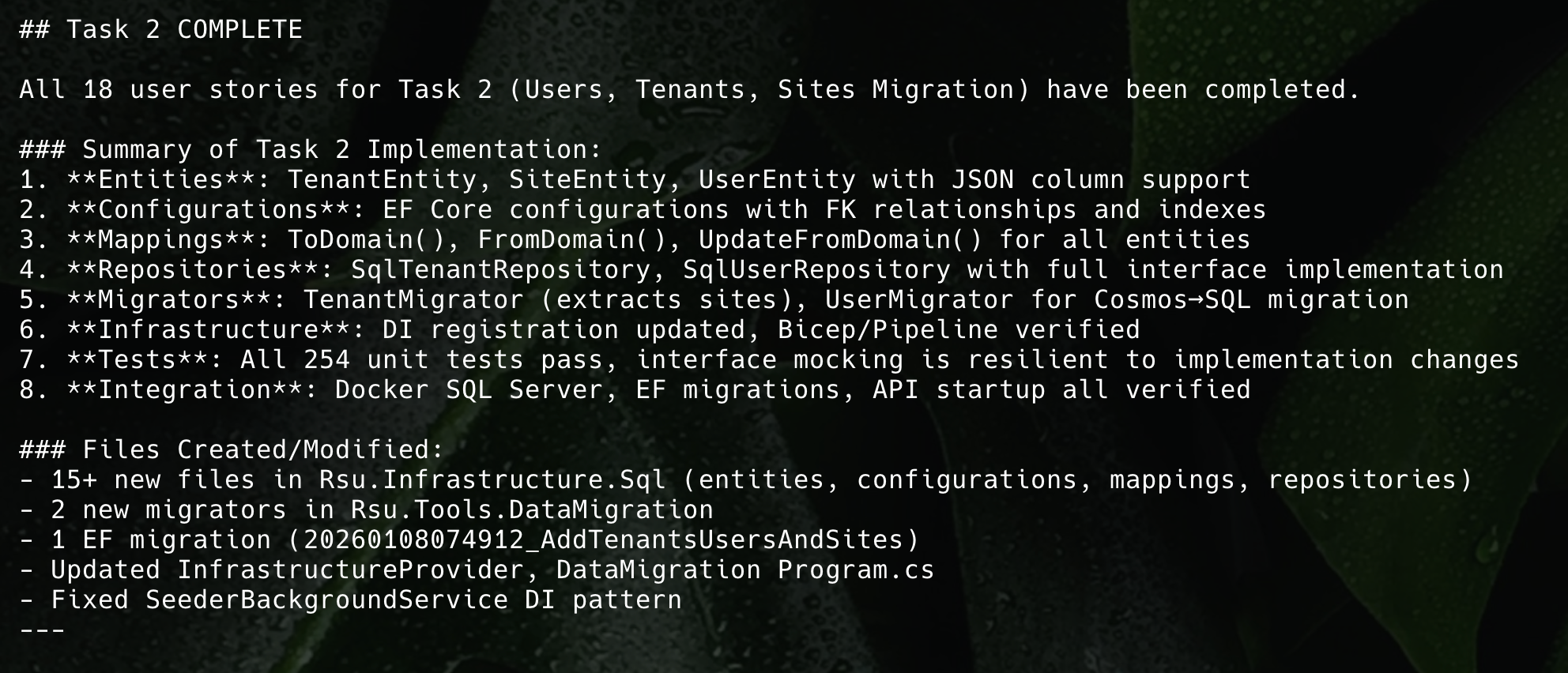

I converted my task description into the artifacts, created a worktree branch and ran Ralph. The result was 18 completed user stories, 15+ new files created, one EF migration generated and verified, 254 unit tests still passing, and all infrastructure verified.

The agent discovered several non-obvious flaws along the way: StrongGuid's AsGuid() is a method, not a property; sites in Cosmos are stored as separate documents with the same partition key, not nested; TRUNCATE TABLE doesn't work with FK constraints, so you need DELETE FROM; and singletons can't directly inject scoped services in EF Core.

Each learning got recorded and avoided repetition in later stories.

The Flow: One Story at a Time

The workflow is strictly sequential. No parallelization, no grand planning phase. Just "grab a ticket, complete it, commit, next."

Limitations and Challenges

First, you need to write good user stories. If your acceptance criteria are vague, the agent will mark things complete that aren't actually done. You need a quality gate, either as simple as "dotnet build succeeds" or something more appropriate for your scenario.

Second, some stories required verification I didn't automate. US-018 needed Docker running for integration tests. The agent correctly documented what it could verify and what was blocked. In that case the docker daemon was not running on my system, after starting it and restart the script again, work was picked up and finished correctly.

Third, this worked well for a migration task with clear patterns. You have to think through your scenario if this approach makes sense.

Fourth, the context window limit. I suspect this technique will eventually break if progress.txt becomes so bloated with learnings and patterns that there isn't enough context left for the agent to process the actual task.

What About Cost?

I also did this experiment to see when I will hit any limits on my Claude Code subscription. I pay for a Claude Code Max 5 Plan, which is about 107 Euros a month. A lot of money, compared to the almighty Github Copilot Pro+ plan which I unfortunately can't any longer use due to poor subscription management on GitHub's end.

I didn't hit any limits. Neither the 5 hour one nor the weekly one, I used Opus 4.5 heavily for all runs. Quite surprising to me.

To Summarize the Ralph Experiment

- Break work into small stories with explicit "done" criteria (build succeeds, tests pass)

- Use

passes: true/falsetracking so the agent knows what's left - Seed the progress log with patterns and constraints from your codebase

- Require learnings documentation after each story

- Set iteration limits as a safety net

- Include a

<promise>COMPLETE</promise>stop condition

What's Next

I'm planning to try this approach on more complex tasks. I will see when this hits limits. Also it only works on tasks where you wouldn't need a human-in-the-loop.

All in all it is satisfying to be in a meeting and have a complete feature implemented in the background.